Enthusiasm for private markets has been growing among investors ever since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC, 2007-09). The conjunction of that trend with that event is not a coincidence.

The crisis led to a wave of new banking regulations and laws across the OECD, led by America’s 2010 Dodd-Frank Act. By requiring banks to hold more capital against their loan books, these rules restricted the banks’ ability to lend freely, especially to higher-risk borrowers such as start-ups and new technologies.

Given the storied resourcefulness of the finance sector, combined with technology’s growing need for capital, it should not have been surprising that new lenders and investors rushed to fill the gap left by the chastened banks.

Additionally motivated by ever-diminishing returns from bonds and cash, hedge funds and pension schemes led the charge. They were closely followed by both private debt and private equity funds, as well as by other “non-traditional” sources of finance.

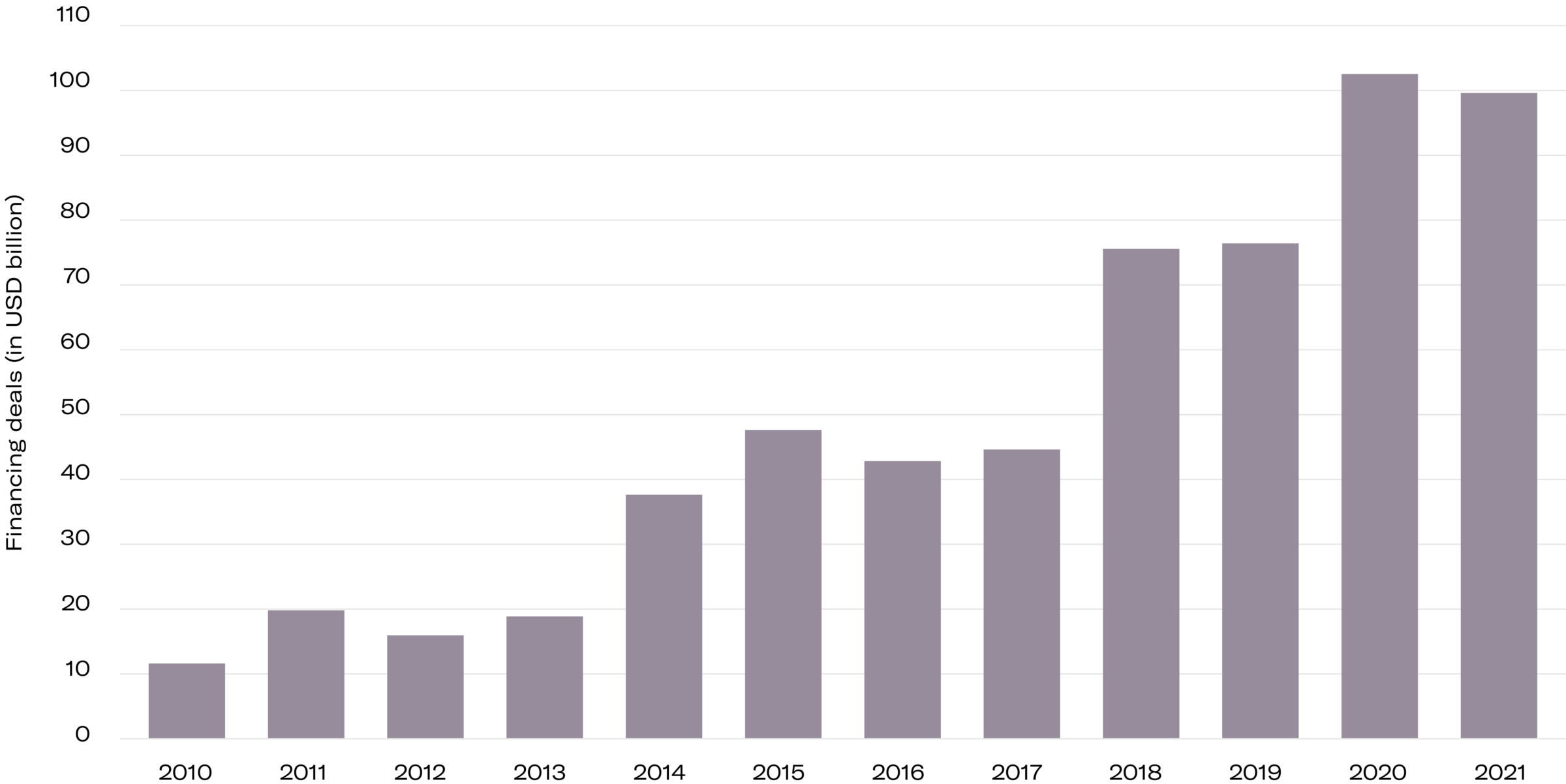

US startups financing deals with nontraditional investors*

Source: PitchBook

* “Nontraditional” refers to lenders and investors who are not banks or venture capital firms.

Private debt had started growing since the early 1990s, a period of significant bank consolidation, which had a profound impact on the supply of capital to small and medium-sized companies. However, the Global Financial Crisis was a turning point in both the American and European markets.

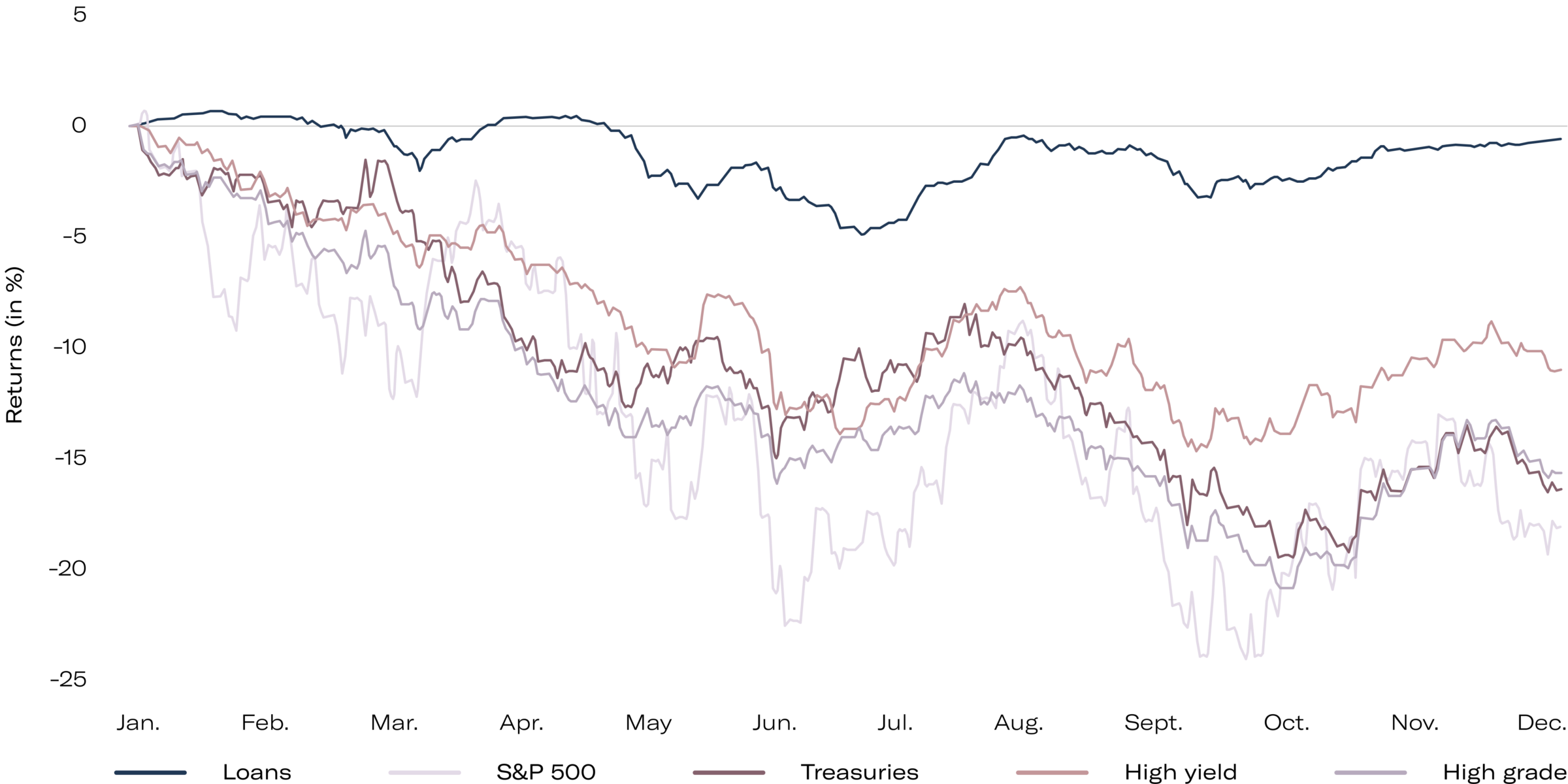

And now the private debt has caught investors’ attention again. After the worst-ever year for public markets, loans has outperformed stocks and bonds for just the third time in 25 years. According to the PitchBook, The Morningstar LSTA US Leveraged Loan Index returned -0.6% for 2022, compared to -15.7% for high-grade corporate bonds and -18.1% for the S&P 500.

2022 cumulative returns by asset class

Source: PitchBook

What, then, is private debt, also – and confusingly – called private credit and is it worth your attention? Essentially, it’s the provision of debt finance to companies, projects, and funds by almost anyone other than banks or the bond markets. As with private equity, there are various strategies, but also various instruments, each with its own risk characteristics.

Note: For this article, peer-to-peer lending (P2P) is excluded from consideration as private debt. It is mainly a retail facility, involving relatively small transactions, and the focus here is on the professionally-managed investment funds that dominate private debt.

Let’s take a look at some of the most common ways to invest in private debt and consider whether they are worth it or not.